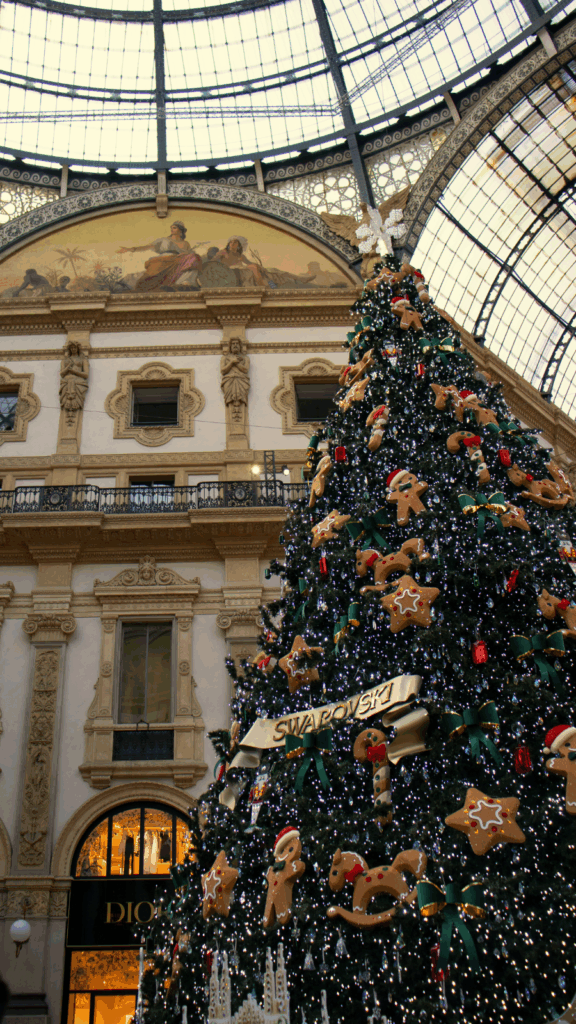

Most people measure Milan in days. They arrive for the opera, leave the next morning, and chalk it up as an evening. But if you stay through January 6, the city reveals something different—a place where private luxury and centuries of public ritual collide, where you move from the inside of La Scala to the streets where pilgrims have walked since 1336.

It’s not a vacation. It’s a calibration. By the time you leave, you’ll have experienced Milan as both insider and witness, which is the only way to understand it.

December 31: The Evening That Starts at La Scala

Five o’clock on New Year’s Eve. You’re seated in the dress circle at Teatro alla Scala, watching the orchestra take their positions. Kevin Rhodes, conducting his twenty-fifth season with the Traverse City Philharmonic and former principal ballet conductor at Vienna State Opera, walks onto the podium with the kind of quiet command that comes from decades of making dancers move to music rather than the other way around.

The lights dim. Tchaikovsky’s Sleeping Beauty begins.

What makes tonight different from any other Sleeping Beauty is the Nureyev production itself. Nureyev wasn’t just dancing the Prince when he choreographed this in 1966—he was writing a conversation with Tchaikovsky, inserting moments that sit like questions in the middle of the ballet. The Prince isn’t just showing off. He’s wrestling with music that doesn’t quite match his body, that insists on things his legs have to solve.

By the finale, when the entire company moves in complex patterns—every dancer doing the same steps, pairs in perfect synchronization—you’re watching something Nureyev left behind that works. The choreography reveals character through precision. The Prince isn’t just glad to be awake. He’s been transformed by what he’s endured.

The performance ends around 8:00 PM, which is precisely when Milan’s New Year’s Eve really begins.

After the Curtain: Il Foyer and the Cenone

Il Foyer alla Scala sits directly beside the theatre, the evolution of Gualtiero Marchesi’s legendary Marchesino restaurant that operated from 2008 to 2020. Redesigned and reopened in its current form, it functions year-round as the theatre’s restaurant. But on December 31, it becomes a moment of deliberate pause.

You can go there immediately, still in the afterglow of the ballet, for prosecco and small plates while other people are still deciding where to spend their evening.

What happens after that is where your relationships matter. The cenone—that elaborate, multi-course New Year’s Eve dinner that Milan takes seriously—is booked months in advance at the restaurants that do it properly. But there are restaurants that keep tables available for exactly these moments, held for clients who understand the value of flexibility.

A table at midnight. Lentils with pork sausage, because tradition says this brings wealth. Courses that unfold without hurrying. The kind of dinner where midnight arrives naturally, not as an interruption.

By 1 AM, you’re somewhere warm, with someone who matters to you, and you’ve experienced the most exclusive theatre in Italy without any of the New Year’s Eve circus. That’s the architecture of the evening.

January 1-5: The City Breathes

This is where most visitors make a mistake. They rush to see things they could photograph from anywhere. But Milan in the days between New Year’s and Epiphany is different—quieter, slower, not performing for anyone.

The Duomo itself. Everyone sees it, but on January 2 or 3, when the tourist logic is still scattered between holidays, you can sit inside long enough to actually understand the building. The scale is meant to overwhelm. The light through the windows at different hours changes how the stone reads. You’re not checking it off. You’re letting it reset something in how you think about space and aspiration.

The Navigli district without a plan. The canals still exist if you know where to look, and the restaurants along them are where actual Milanesi eat—not tourists performing the idea of being in Milan. Lunch is simple. It’s not about appearing to have sophisticated taste. It’s about what’s good that day.

The Triennale di Milano is open and essentially empty. The permanent collections show how Milan thought about the relationship between making things and living with them—and it’s more honest than most design museums because it includes mistakes, failed experiments, things that didn’t last. That honesty is worth more than another cathedral.

Find a café where locals actually sit. Spend an hour there with coffee and a newspaper you don’t understand. Watch how people move through the city when they’re not tourists. The rhythm is different. Less rushed. More settled into winter.

January 6: The Procession and What Happens Beneath It

By January 6, you’ve been in Milan long enough that the city feels like something you inhabit rather than something you’re seeing. This is exactly the right state of mind for Epiphany.

The Procession Itself

The procession is public. That’s part of the point. Three figures in medieval costume representing the Magi will walk from the Cathedral to the Basilica of Sant’Eustorgio, a route that’s been walked since 1336. There will be crowds. There will be pilgrims and tourists and locals and schoolchildren. It’s ceremonial and slightly chaotic and genuinely moving if you understand what you’re watching.

What Most People Don’t Know

Sant’Eustorgio isn’t just a destination for the procession. It’s one of Milan’s oldest churches, and its history is genuinely strange.

The basilica was founded in the 4th century by Bishop Eustorgio specifically to house the relics of the Magi Kings—the bodies of the three wise men who followed the star to Bethlehem. For over a thousand years, these relics made Sant’Eustorgio one of the most important pilgrimage sites in Europe. People traveled across continents to venerate them.

Then, in 1164, Frederick Barbarossa himself seized them during his conquest of Milan, relocating them to Cologne. Milan lost one of its primary reasons for significance.

This is important context. By the time January 6 rolls around every year, Milan is essentially honoring a theft that happened over 850 years ago. The procession walks to a church that houses only fragments of the relics—the pieces that were returned in 1903-1904 through Cardinal Ferrari’s intervention. It’s ritualized memory of loss and partial recovery.

Inside Sant’Eustorgio

The church itself, if you visit it when the crowds have moved on—late afternoon, after the processional energy has dissipated—shows you something about how medieval Milan thought.

The apse is decorated with a 14th-century mosaic that’s been restored and restored again. The brick is visible. The stone shows wear. There’s no attempt to make it pristine. It looks like something that’s been used, maintained, walked through, prayed in, survived. That matters. It’s the opposite of museum thinking.

There’s also a museum inside Sant’Eustorgio that houses works from the surrounding region—not masterpieces that would make you travel across the world, but real objects that tell you how people lived and what they valued. The kind of place where you can spend two hours without feeling like you’re consuming art.

Look up at the bell tower as you leave. Unlike every other church in Milan, there’s a star at the top instead of a cross—marking the presence of the Magi relics that once resided here, and the fragments that remain.

Then, as evening falls on January 6, you leave. The Epiphany takes all the holidays away, as Milanesi say. Winter proper begins. The city returns to itself.

The Gift of the Week

What you’ll realize by January 6 is that Milan doesn’t work in isolated experiences. La Scala on December 31 is extraordinary, but it only makes sense within a week that also includes watching a 688-year-old procession walk to a church that lost and partially recovered its most precious objects.

You’ve experienced Milan as the wealthy do—private, curated, inside rooms that matter. You’ve also experienced it as the city actually is—public, ceremonial, connected to centuries of memory that have nothing to do with luxury.

That duality is the real thing about Milan. Not the opera. Not the architecture. Not the fashion. But the ability to move between those two worlds in a single week and understand that they’re not separate—they’re two aspects of the same place.

A Note on Arranging This

If you want to experience that week, we can arrange it. Not as a package, but as what it actually is: a calibration of your attention toward a city that reveals itself slowly.

The La Scala performance on December 31 requires advance booking—these seats are claimed months ahead. Il Foyer takes reservations but also holds select tables for regular clients who understand timing. The cenone requires relationships with restaurants that don’t advertise their New Year’s availability publicly.

The Epiphany procession is free and public, but experiencing Sant’Eustorgio properly—understanding its theft narrative, seeing the museum when it’s not crowded, standing in the right light to see how the mosaics read—requires knowing when to arrive and which corners matter.

This is what we do. We don’t create spectacle. We create access and context so that a week in Milan becomes something that recalibrates how you see cities, ritual, and the relationship between private luxury and public memory.