The Constraint Is the Point

You won’t find fresh artisanal panettone in July. Production stops December 26 and doesn’t restart until September. Right now, in late November, you’re in the only window where the real thing exists.

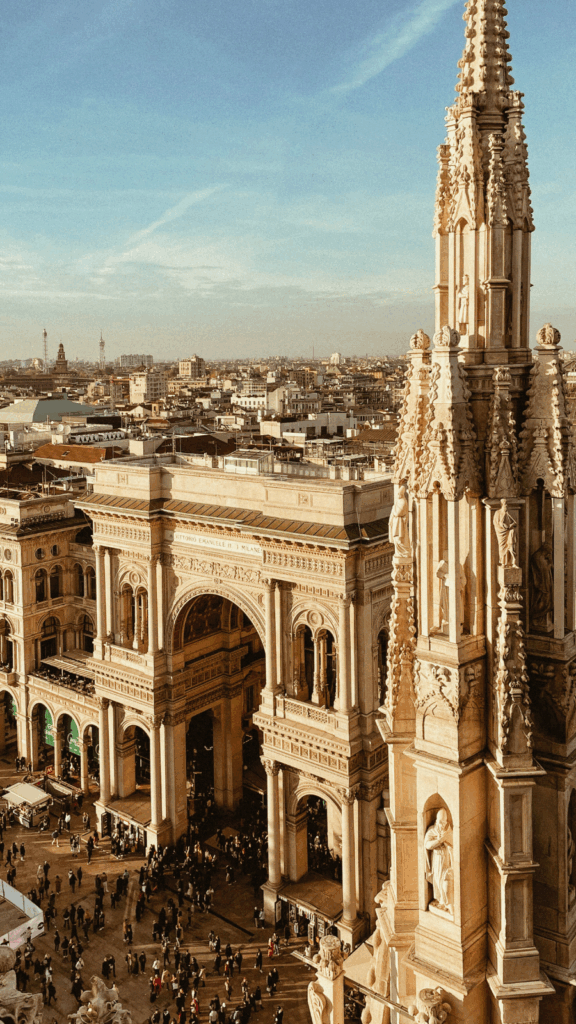

And it only truly exists in Milan.

Not because of climate or water or some geographic accident. Because Milan made a choice four centuries ago and never unmade it.

How Milan Said No to Everything Else

When medieval traders brought spices through Milan raisins, candied citrus, vanilla they arrived in a city wealthy enough to control what would happen next. At Christmas, bakers received special permission to use wheat flour (normally reserved for the rich). They combined it with the expensive imports they had access to, creating one bread for one celebration.

By the 1500s, this was the bread. A statement about what Milan valued.

Then came the 1920s. Angelo Motta industrialized panettone. He solved every problem: shelf life, distribution, profit margins. Other cities followed. Rome optimized. Naples optimized. The industry standardized.

Milan’s family bakeries Cova (1817), Marchesi (1824), Cucchi (1936) refused. Not out of stubbornness, but conviction that some things shouldn’t scale. They kept natural fermentation, seasonal production, three-day processes. They accepted closure for nine months. Small operations. Customers who came to them.

Milan was wealthy enough to afford this. And wealthy enough to understand: what they were signaling mattered more than what they were producing.

The Bakeries That Refused

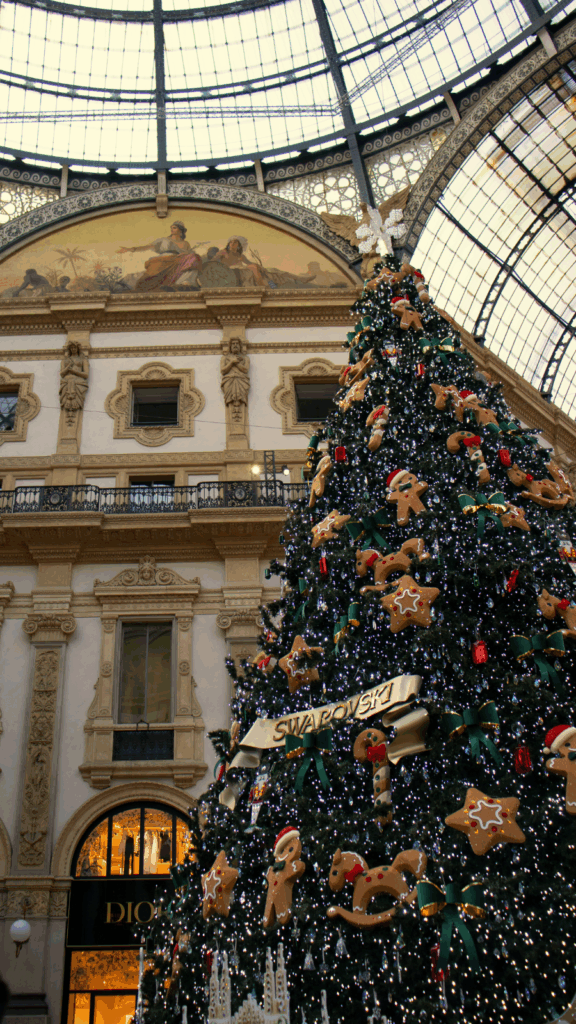

Pasticceria Cova sits steps from La Scala. After performances, Verdi and Puccini came here to eat panettone and argue about art. In 2014, Prada acquired it and chose not to change anything. The Belle Époque space remains untouched. Their “Le Donne dell’Opera” collection wraps panettone in sketches from historic opera costumes—honoring the building’s past, not redesigning it. You can taste slices before committing.

Pasticceria Cucchi is the opposite—no design narrative, no performance. Ticinese neighborhood, vintage unchanged, 89 years of the same family refreshing the same starter culture. Every single day for 89 years. Walk in and you’re in a working bakery. No website. No performance. Just: we’re here if you want this.

Marchesi 1824 signals something different—designed, confident, beautiful. Award-winning. The soft-pink packaging became how Milanese say “I understand what matters.” This is where people buy panettone to give as gifts.

Pavé is the contemporary answer—young enough to innovate (creative flavors, geometric design), disciplined enough to hold the three-day natural fermentation. Six locations across the city.

What You Actually Do

Visit bakeries during production season—late autumn through early January. Go early morning. Taste multiple locations. Notice what’s different about each space, not just the panettone. The atmosphere. The choice each bakery made about what to preserve.

Plan two hours tasting across the city.

Then You Actually Taste It

Panettone isn’t complicated: butter, flour, yeast, candied fruit, raisins. The magic is in time.

Natural fermentation is unpredictable. The yeast doesn’t follow a schedule. The baker adjusts. Three days becomes three and a half if the climate is cold. The texture develops differently in winter than summer. After eighty-nine years, the baker knows this.

Industrial panettone solves this problem. Controlled temperature, precise timing, consistent result. Shelf-stable for months. Profitable.

The natural version tastes like time. Finer crumb. Stays moist for days instead of drying out. The flavor is integrated—the way things taste when they’ve had time to become themselves.

You’ll notice the difference.