You’ve seen European summer. Every travel magazine shows you the same version: golden light, outdoor markets, wine terraces, people who aren’t bundled in coats. It’s beautiful. It’s also a performance.

Winter is different. Quieter. Less forgiving. And absolutely revealing.

That’s when you learn what Europeans actually eat when no one’s watching. When the tourists leave and the markets shift. When ingredients arrive that only the cold brings. When tradition isn’t performing for an audience it’s just living.

This isn’t about Christmas markets (though they’re there). It’s about what happens after the ornaments come down. What people cook in January. What a culture chooses to eat when survival isn’t the question anymore taste is.

We’ve spent years arranging experiences across Europe. We’ve learned five regions where winter food reveals something true. Not romantic. True.

Alsace: The Calendar Lives in Bread

December 6 arrives and Mannele appears in every bakery. A brioche shaped like a little man, dusted with pearl sugar. This is the region marking winter’s start through bread the moment when tradition shifts from summer memory to winter ritual.

By mid-December: Bredele. Dozens of varieties anise cookies, cinnamon stars, almond tiles. Each bakery has recipes no one else uses, taught mother to daughter. These are social currency. You give them as gifts. You keep them until January because they’re meant to last.

Then Berawecka. A dense brick of pears, figs, nuts macerated in Schnapps. You eat it in thin slices with cheese and coffee. Never quickly.

The shift: Christmas markets are glühwein and shopping energy. When the tourist crowds disperse, the Koïfhus opens its Gourmet Market where locals eat instead of shop. Bouchée à la Reine: puff pastry filled with veal, mushrooms, cream, served with Spaetzle. You eat standing, steaming, your other hand free for mulled wine.

Then the chef enters the conversation.

Olivier Nasti at La Table d’Olivier Nasti (2 Michelin stars, Kaysersberg) doesn’t abandon these traditions he inhabits them. A Meilleur Ouvrier de France, Nasti personally hunts wild game in the Kaysersberg mountains, 20 minutes from his restaurant. His philosophy: “The chef’s objective is to showcase the terroir and restore tradition in a series of creative, visually arresting, even playful dishes.”

During his November “Hunting Festival,” Nasti serves what he’s killed and preserved: game from “our mountains” with rosehip and juniper oil, hot game pâté with fermented black fruits, candied Williams pear with roasted chestnut ice cream. He describes his approach as “classic and creative at the same time today it represents contemporary Alsace.” The preserved fruits you see at Christmas markets become his autumn inventory. He sources the same Bredele tradition from local bakers, then reimagines it through technique. This isn’t rejection of tradition. This is living it.

How to taste it: Time your visit to catch when Mannele first appears. Book with Nasti when his November “Hunting Festival” menu is active this is when he reveals his relationship with local hunters. Visit wine bars along Strasbourg’s main streets for small pours and charcuterie paired alongside Riesling. Ask which bakeries are worth visiting early morning. When you eat Bredele at a Christmas market, photograph it and remember which flavors you found essential. Then ask Nasti if he works with similar producers.

Dordogne: What Winter Gives

The black truffle season opens November 1 and runs through March. A truffle hunt happens before dawn you arrive at a forest edge with a trained dog, walk in cold darkness, the dog stops, you dig, and ten centimeters down is a black knobbed fungus. Two hours of work. Three or four truffles. €800-1500 per 100 grams. The hunt explains why.

But the real understanding comes when you eat it. Shaved over hot pasta with simple butter and maybe sage. The aroma is immediate funky, earthy, slightly sweet. You eat it slowly because rushing would be disrespect.

Foie gras season runs November through January. Visit a producer (not a shop). Taste raw liver seared quickly the texture is butter, the flavor rich and almost sweet.

Game season (November through winter): Wild boar, venison, duck at restaurants and butcher stalls. A good brasato takes six hours—the meat dissolves, the wine becomes sauce.

Bergerac wines are often overlooked. Visit a small producer when they’re relaxed. They’ll pour barrel samples.

Then the chef reveals what this region actually means.

Pascal Lombard at Le 1862 – Les Glycines (1 star, Les Eyzies) comes from a Landaise family his connection to this region is genealogical, not career-based. The restaurant maintains its own beehives, kitchen garden, and sources trout from the Vézère river itself. His relationship to local hunting traditions isn’t theoretical. He has “a strong bond with the local producers who provide the essential basis of his cuisine. He tries to express the character of the terroir and its products.”

The foie gras you taste at a Christmas market, the game, the preserved fruits—these are his morning’s work. When you eat at his table, you’re tasting what the region actually produces, not what it performs for tourists. His approach is rooted in understanding that Périgord was “one of the first places to conserve meat: once you’ve used the liver and the duck breast, they thought, what are we going to do with the rest?” This is luxury born from necessity.

How to taste it: Arrange a truffle hunt in advance through a local guide. Eat your truffle that same night at Les Glycines confirm when booking that Pascal sources fresh truffles that day. For foie gras, visit a producer and ask about production methods. Book a Michelin dinner where the menu is built around what the hunters brought that day. The chef is sourcing from the same operations you’re experiencing.

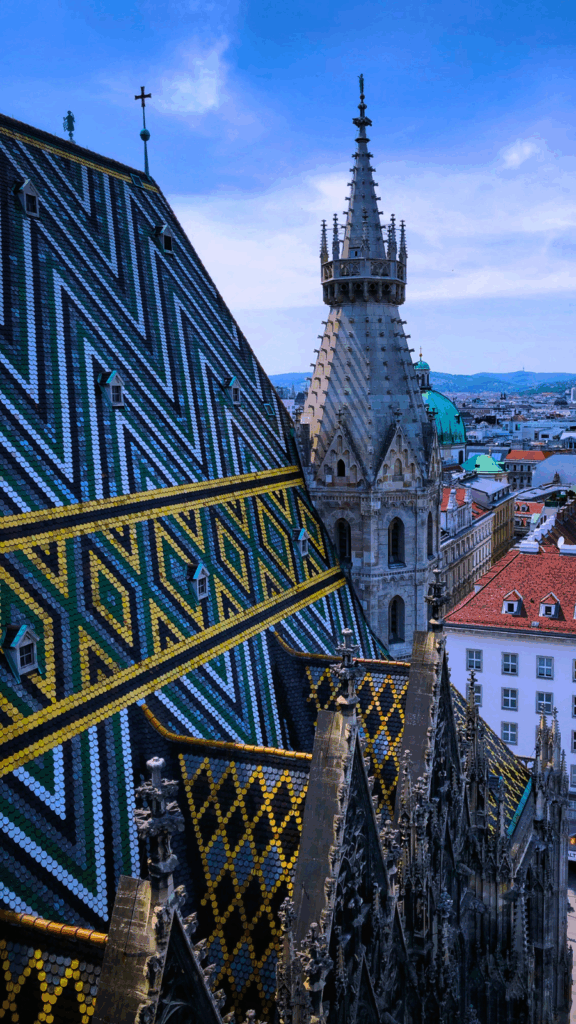

Vienna: When Order Becomes Comfort

When Christmas markets officially close, Vienna reorganizes itself. Vienna is saying: we’re moving from celebration of what was to preparation for what’s coming.

Kaiserschmarrn—Emperor Franz Joseph’s favorite breakfast—is shredded sweet pancake with plum compote. It sounds simple because it is. It’s comfort that proves you don’t need complexity.

Strudel (apple) requires technique—pastry stretched thin enough to read through, filled with apples, cinnamon, raisins. You eat it warm with vanilla sauce or whipped cream and coffee. Precision is the luxury.

Punsch is everywhere in winter—mulled punch in ceramic mugs. Orange, berry, herbal varieties. You drink it slowly, standing, usually with strangers.

Then the chef reveals what tradition can actually become.

Heinz Reitbauer at Steirereck im Stadtpark (3 stars, ranked #33 on World’s 50 Best) became Vienna’s third three-star restaurant in January 2025. Named “Chef of the Decade” by GaultMillau in 2016, Reitbauer states: “At Steirereck, we are constantly searching for the flavours and tastes of our country because they create a connection—to our families, our homeland, and our culture.”

His philosophy is rigorous: “I believe we can only produce a cuisine that is authentic, sustainable and noteworthy in the long term if we engage with the products that are available in our country.” His modern goulash with spelt and medlars transforms the market-stall dish into something that honors its lineage. His veal lights (Beuschel) with chive dumplings—a traditional offal dish—becomes a meditation on using the whole animal. His char cooked in beeswax demonstrates how regional preservation techniques become cooking method. He maintains a 4-hectare biodynamic farm at Pogusch in Styria, a rooftop herb garden, and sources citrus from Schönbrunn’s imperial orangery. This is tradition built on infrastructure, not nostalgia.

How to taste it: Time your visit during Vienna’s formal transition from Christmas markets to winter dining—this shift is real and worth experiencing. Eat Kaiserschmarrn at a traditional café in the morning; the ritual matters. Book a Michelin dinner at Steirereck specifically. When you eat Strudel at a market, ask which bakery made it. Then ask Reitbauer about his approach to the same dish. The conversation will tell you everything about how Vienna thinks about tradition.

Piedmont: The Philosophy of Stopping

The white truffle of Alba only grows October through December. Peak season is November. It smells aggressive—funky, earthy, slightly sweet, slightly sulfurous. The flavor is delicate by comparison. Almost waxy.

Alba knows how to use what it has. You won’t find white truffle risotto drowned in cream. You’ll find risotto with butter and sage, topped with a thin shaving of truffle. The truffle is the star. This is what Piedmont understands: sometimes less is everything.

The Alba truffle market runs October through December. You can buy directly from hunters who arrive before dawn. Good ones smell intense.

Tajarin—paper-thin egg pasta, Piedmont’s signature—is the perfect vehicle. Butter, sage, maybe a touch of parmesan. Then the truffle, shaved thin. Ten minutes to cook. Years to perfect.

Barolo wine comes from grapes grown in the hills surrounding Alba. The season is when new-release Barolos arrive. The wine is deep, complex, built for time. You don’t rush it.

Then the chef articulates what this region’s philosophy actually is.

Enrico Crippa at Piazza Duomo (3 stars, ranked #32 on World’s 50 Best) is perhaps Europe’s clearest voice on restraint. When asked whether designing a truffle menu overshadows his talents, he replied with one sentence: “White truffle is the king.”

During autumn’s 8-course truffle tasting menu (€290 plus supplement), Crippa deliberately “puts away his glamour,” presenting ingredients minimally so the truffle’s essence dominates. But his deeper genius lies in a 4-hectare biodynamic garden with 400+ plant varieties at Tenuta Monsordo Bernardina, where he personally harvests ingredients every morning at 7:30am. He works with a trusted truffle supplier who irrigates their land during dry seasons—the kind of relationship built over decades, not transactions. This is how you respect tradition: by understanding it so thoroughly that you know exactly when to step aside.

How to taste it: Time your visit during peak truffle season when the best hunters are at market early morning. Walk the Alba market and smell everything. Book a dinner at Piazza Duomo and ask to see and smell the truffle before you order. Visit a small Barolo producer (rolling hills, about 90 minutes from Turin). The owner will sit with you. Return for dinners taking gastronomy seriously. Eat brasato. Drink Barolo. Understand what this region values: depth, age, simplicity, quality over flash.

Bruges: When Staying Still Is the Radical Act

Bruges doesn’t have a seasonal ingredient. It has artisans who refused to leave.

Dominique Persoone is a chocolatier who invented the Chocolate Shooter—a device that lets you inhale cocoa powder mixed with spices. It’s provocative. It’s exactly what tradition needs: someone brave enough to ask, “What if?” His shop, The Chocolate Line, is in Bruges. His cocoa comes from his own plantation in Mexico. He doesn’t franchise.

De Halve Maan Brewery has been brewing in Bruges since 1856. Six generations. Recently, they built a 3km underground pipeline to move beer to a bottling facility outside the city. Why? Because they refused to leave. Their beer, Brugse Zot (“The Fool of Bruges”), is a golden ale distinctly rooted in place.

Otto Waffle Atelier makes waffles inspired by Bruges’ lacework tradition. Someone decided tradition could be reimagined.

The Christmas markets sell chocolate, waffles, mulled beer. This is Bruges performing for tourists.

Then the chef reveals what Bruges actually is.

Filip Claeys at De Jonkman (2 stars plus Green Star, Sint-Kruis) represents the fullest integration of local artisans into haute cuisine. Her beer credentials are explicit: “Our Trappist beers are fantastic. They are known and appreciated worldwide.” She won “Best Beer Menu” from GaultMillau in 2020 for a reason.

Her langoustine with white beer mousseline and crispy fried hop shoots demonstrates how Belgian brewing traditions elevate rather than overpower refined cuisine. But here’s what matters: Dominique Persoone’s The Chocolate Line creates custom chocolates specifically for De Jonkman’s dessert courses. Claeys founded NorthSeaChefs to promote sustainable fishing and works with a single fishing boat (Z571) for her North Sea catch, sources Ostendaise Oysters from Belgium’s only oyster farm, and maintains on-site beehives. She’s not using local ingredients because it’s trendy. She’s using them because she’s built a life here.

When you eat at De Jonkman, you’re tasting beer from De Halve Maan that you walked past that morning. You’re eating chocolate from Dominique Persoone’s hands. You’re eating oysters from a farm 20 kilometers away. Bruges isn’t performing. It’s just living, at the highest level.

How to taste it: Visit The Chocolate Line and pick something that intrigues you. Take a tour of De Halve Maan Brewery and taste Brugse Zot fresh from the source. Eat waffles at Otto Waffle Atelier and ask about today’s toppings. Book a Michelin dinner at De Jonkman specifically—confirm that Dominique Persoone is providing custom chocolates for that week. Spend evenings walking the canals at dusk. This is what Bruges offers: permission to move slowly in a city that chose to stay still.

What These Five Teach

Let’s talk about when you want to go. Let’s figure out which region calls to you. Let’s build an experience that isn’t performed—it’s lived.

Reach out. We’ve been doing this long enough to know the people worth meeting, the moments worth waiting for, the food worth traveling for.

The rest of Europe is fine in summer. Winter is when the real story begins.