You’ve stood in enough museums that the hush feels familiar now. You know the angle of light through stained glass. You’ve learned to read a room full of people pretending to understand something they’re looking at.

But you haven’t watched a painter step back from a canvas at 4 p.m. and say, quietly, “I don’t know if this works.” Haven’t sat across from someone who made the thing you’re eating and heard them describe why they changed it three times. Haven’t been in a studio where someone is still deciding—where the work isn’t polished into meaning yet, but alive with doubt and revision.

That’s different. That’s not tourism.

In these five cities, art didn’t get swept into institutions and settled. It stayed in the streets, the kitchens, the back rooms where people are still asking questions about how to live. Where a gallerist will tell you a piece isn’t ready. Where a chef treats a plate like a conversation that’s still unfolding. Where you can actually be present for something real instead of something already decided.

The luxury isn’t access. It’s being in a room where the thinking is still happening. Where you’re not admiring finished work—you’re witnessing work in its most honest moment.

That changes everything.

Paris: The Private Circuits Nobody Tells You About

Paris doesn’t reveal its best art by asking nicely at the front desk.

Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac has two spaces—one in the Marais (7 Rue Debelleyme), another in Pantin just outside the city. Both operate at museum scale. You’ll catch conversations between artists, curators, and collectors that sound nothing like typical gallery talk. Someone’s arguing about scale. Someone else is questioning whether the work is even finished. The gallerist is standing back, letting it happen.

Go in the morning. The light is different. The space feels inhabited, not staged.

Stay at Villa Junot, a 1920s townhouse in Montmartre that’s been restored as a private residence. This is where the Surrealist moment actually lived—the space is charged with Art Deco geometry and Surrealist sensibility woven into its bones. The rooms are small, intimate, designed with the same precision and playfulness that defined the artistic movement happening just outside its doors. You’re not checking into a hotel; you’re living inside the era you came to understand. The windows face a courtyard that’s genuinely quiet, which in Paris feels like a small miracle. Sleep here, then walk out into Montmartre and suddenly the art from that period makes different sense. You’re seeing it from inside the world that made it.

For real depth, skip the standard museum circuit. Instead, arrange a private visit to the Musée Delacroix, Eugène Delacroix’s preserved studio-apartment tucked into the 6th arrondissement. Most people never find it. When you do, you’re standing in the actual space where he worked—his brushes still there, his sketches still pinned to walls, light coming through windows exactly as it did in the 1850s. It’s not grand. It’s intimate in a way museums never are. You understand, standing there, that he was a person solving problems with paint, not a historical figure.

Then there’s the Musée Guimet, which most visitors skip entirely. It’s enormous, overwhelming, and full of masterpieces from South, Southeast, and East Asia that somehow feel less visited than they should be. Arrange for a curator-led tour. Tell them you’re interested in the way the collection was assembled, not just the objects. The colonial history, the taste, the eye of the collector. It changes everything.

Dinner matters here, so don’t make the mistake of seeking out three-star theater. Go to Le Baratin in Belleville (3 Rue Jouye-Rouve), run by chef-owner Raquel Carena, who pioneered Paris bistronomie and still cooks from instinct rather than a recipe. The wine list reads like someone’s personal cellar—natural, idiosyncratic, alive. Sit at the bar if you can. Watch her work. This is what Parisian cooking actually looks like when it’s not performing for critics.

The move here: stay longer than you think you need to in one neighborhood. Let it become familiar. The art happens in the margins, in the spaces between the famous landmarks.

Tuscany: The Moment Before It Becomes a Museum

Tuscany has a problem: everyone expects it to be beautiful in a particular way. Manicured. Picturesque. Safely historical.

The actual art scene here is more interesting because it’s fighting that expectation.

Skip Florence. Don’t rent a villa in Chianti. Instead, base yourself at Rosewood Castiglion del Bosco in the Val d’Orcia—a UNESCO landscape where the light genuinely does something to your perception. The estate is a restored 14th-century village, which means the architecture is real, not reconstructed. Medieval stone, actual history baked into the walls. The contemporary comfort is there (you’ll sleep well), but it doesn’t interrupt the sense of being somewhere genuinely old. More importantly: you wake up in a landscape that Renaissance painters spent their entire lives trying to capture. The light moves the same way it did 500 years ago. That changes how you see the paintings when you go looking for them.

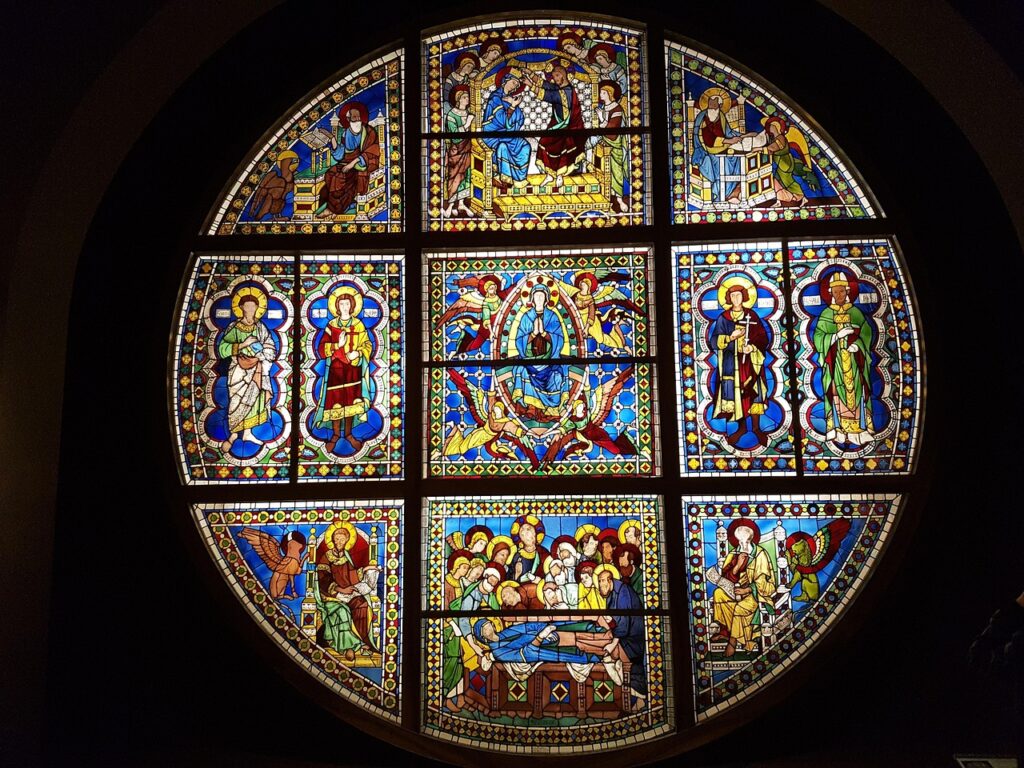

From there, drive to Montepulciano. The Pinacoteca Crociani sits in the town center—a local collection of Renaissance works that originally belonged to local chapels and families. This is the opposite of the Uffizi. There are no crowds. The paintings aren’t contextualized by centuries of art historical argument. You’re looking at what mattered to people who lived here. A Madonna. A saint. Work made by artists whose names are half-forgotten. Stand in front of a 15th-century panel and you feel the weight of local devotion, not global canonicity. It’s a different kind of understanding.

Pienza is next, but skip the cathedral. Go to the Museo Civico instead. It holds 14th–16th century panel paintings that originally lived in the churches surrounding the town. Seeing them here, removed from their architectural homes, is almost tragic—you understand what’s been lost when art gets extracted from context. But you also see the work more clearly because there’s nothing else competing for your attention. Just paint, wood, and time. The colors are still vivid. The figures still hold their dignity. You’re not in a museum. You’re in a room where locals decided to preserve what mattered to them.

The real pilgrimage is Sansepolcro, birthplace of Piero della Francesca. The Museo Civico houses his Polyptych of the Misericordia—one of the most moving works of early Renaissance art still in its original community. Not shipped to Florence, not hung in a major collection. Still there, in the place it was made for. The painting is dense, geometric, almost abstract in its composition. The figures float in a kind of suspended geometry. Stand in front of it for twenty minutes without moving. The longer you look, the more the space between the figures starts to matter as much as the figures themselves. That’s Piero. That’s why he’s worth the drive.

Here’s the thing about Tuscany that matters: the contemporary artists living here now understand this history. They’re not trying to replicate it or escape it. They’re in dialogue with it. Ask your hotel to connect you with working artists in the region—painters, ceramicists, sculptors who’ve chosen to make their studios in these towns. Spend an afternoon in someone’s studio. Watch them work. Listen to them talk about light, about the landscape, about how living alongside 500 years of artistic tradition changes what you make. You’ll understand that making art hasn’t changed fundamentally. It’s still about solving problems in the studio, alone, day after day. The difference is that here, the ghosts of the painters who came before are actually helpful.

Porto & Douro Valley: Where Wine Is Treated Like Art (And Art Like Wine)

The Douro Valley is having a moment—not because it’s been discovered, but because the people living there are actively deciding to build something different from what Tuscany became.

Stay at Six Senses Douro Valley, a 19th-century manor house restored with actual intention. The spa exists, the vineyards exist, but what matters is how the hotel integrates contemporary art into daily life. Sculpture in the gardens. Curated installations in corridors. Art isn’t presented as something to look at in passing—it’s something you live alongside. You wake up, walk past a contemporary piece, and realize you’re learning how to see it by living with it. That’s not a hotel amenity. That’s an education.

From there, the move is to understand that the Douro Valley treats wine the way sophisticated collectors treat art. Precision. Obsession. The belief that terroir—the specific conditions of a place—shapes everything. Ask your concierge to arrange visits to quintas (wine estates) where the owners also collect contemporary art. This isn’t wine tasting followed by gallery time. It’s a single conversation. You’re standing in a vineyard with sculpture in the distance, drinking a wine made from grapes grown in that exact soil, and understanding that both the art and the wine are expressions of the same sensibility. Same commitment to detail. Same refusal to make things easy.

In Porto itself, the real art isn’t in galleries—though galleries exist and are worth visiting. The real art is in the azulejos, the ceramic tiles that cover building facades throughout the city. Walk through the center and you’re walking through centuries of visual culture made tactile. These aren’t museum pieces. They’re part of the streetscape. They’re faded, weathered, integrated into daily life. The Museu Nacional do Azulejo in Lisbon is the formal study, but in Porto you’re living inside the actual tradition. The tiles teach you how to see. The patterns repeat, variations shift, colors fade—and somehow that feels more honest than a preserved piece behind glass.

Spend an evening in Ribeira, the old quarter along the river. End up at a tasca (small tavern) where the food is simple and local. Grilled sardines. Bread. Wine. You’re sitting shoulder to shoulder with people who live here, who don’t speak English, who are eating dinner, not performing tourism. That’s Porto in miniature—no pretense, just living well with what’s available.

Cross the Dom Luís I Bridge at dusk. The bridge itself is a piece of engineering that’s become iconic—double-deck iron structure spanning the Douro. Stand on the upper deck and the city opens beneath you. The light moves across the water. The layers of the city—the old quarters, the new developments, the river working through it all—suddenly make sense. This is what infrastructure looks like when it’s also beautiful.

Dinner is at The Yeatman, a luxury hotel with a restaurant overlooking that same bridge. The cellar is one of the most thoughtfully curated in Europe. Not trying to show off. Just precise, intelligent wine pairings that make sense. Each plate is composed, deliberate. You’re not being entertained. You’re being shown how one kitchen thinks about flavor, texture, the relationship between food and wine. The view doesn’t hurt—watching the bridge light up as you eat is secondary. Primary is the food in front of you.

Here’s what makes the Douro different from other wine regions: it’s not commodified yet. The contemporary art scene is still raw. Galleries are opening quietly. Artists are choosing to work there. The infrastructure is emerging in real time, not preserved as heritage. You’re arriving at the moment before it becomes a brand.

San Sebastián & the Basque Country: Food as Philosophy, Art as Daily Argument

San Sebastián has a secret: it doesn’t care if you know it’s one of the best food cities in the world. It would keep cooking at this level regardless.

Stay at Hotel de Londres y de Inglaterra, a classic Belle Époque hotel directly above La Concha Beach. Wake early and the promenade is empty. The hotel interior—gilt mirrors, sea-facing windows—feels slightly suspended in time. You’re staying in 1890. That’s not romantic nostalgia. It’s practical. A different rhythm than a modern hotel gives you. The pace changes when your room has that kind of history baked in.

Visit Chillida-Leku, the former farmhouse-atelier of sculptor Eduardo Chillida. His monumental iron and granite works are scattered across the fields. The pieces are enormous. Weathered. There’s no climate control, no preservation theater. The sculptures are aging in real time. You watch rust accumulate. Stone cracks. Wind moves through them. This is the opposite of museum culture. This is art being allowed to exist in the world, not be protected from it. Standing in front of a ten-ton iron form in an empty field changes what you think art should look like. Note: Check opening hours before visiting—the space occasionally closes for maintenance.

Tabakalera, a converted tobacco factory in the city center, is the contemporary counterweight. It functions as a genuine cultural space, not a designed experience. Artist residencies happening in real studios. Exhibitions being installed. Film programs running. Go on a weekday afternoon when tourists are elsewhere. You’ll see the actual infrastructure—artists working, conversations happening, the machinery of contemporary culture. It’s not curated for your consumption.

Here’s where San Sebastián reveals itself: the art doesn’t live in galleries or museums. It lives in the bars.

Join a local guide for a pintxo tour through the Old Town’s iconic bars. A pintxo is a small dish—usually one or two bites—served on a bar counter. But these aren’t appetizers. Each one is a composition. Watch the bartenders work. They move with precision and speed. A squeeze of lemon. A precise placement of pepper. A deliberate balance between salt and acid and richness. This is art. Not food that aspires to be art. Actual art, the way the Basques understand it. The philosophy is identical whether you’re looking at a Chillida sculpture or a pintxo: precision, respect for materials, no shortcuts. No decoration hiding weakness. Just the thing itself, done perfectly.

You’ll understand this more clearly at Akelarre, Pedro Subijana’s three-Michelin-starred restaurant overlooking the sea. The food is extraordinary, but what matters is the thinking behind it. Each dish is testing an idea. Each course is part of an argument about flavor, texture, memory. Subijana isn’t trying to impress. He’s trying to communicate. You’re not being entertained. You’re being shown how one mind thinks about cooking. The view—the water, the light—is secondary. What you’re actually consuming is the precision of the thinking.

This precision shows up everywhere. Outside the city, in Astigarraga, visit a sagardotegi (cider house) like Petritegi. Stand in a room full of wooden barrels. Eat grilled txuleta (steak) cooked over an open fire. The meat is exceptional because the cider house sources it with the same care Subijana applies to his three-star kitchen. Drink cider poured from height into glasses—a deliberate pouring technique that has been refined over centuries. This isn’t rustic nostalgia. It’s precision applied to communal eating. You’re sitting at long wooden tables with strangers, eating alongside locals, and understanding that the Basques don’t distinguish between “fancy” and “authentic.” They just demand excellence from whatever they’re doing.

The move here: understand that art and food and daily life aren’t separate categories in this region. They’re one continuous conversation about how to live well. The same discipline, the same obsession with detail, the same refusal to make things easy just runs through everything.

Basel: The Art City That Actually Lives

Basel is compact, which means you can feel the density of the art infrastructure almost immediately. But don’t come during Art Basel week unless you want spectacle and crowds. Come when the city is just itself.

Stay at Hotel Euler, a 19th-century establishment on Centralbahnplatz. It feels genuinely used by actual people, not designed for hotel guests. The interior is dignified without being frozen. You’ll be comfortable. That’s the entire point. Walk out the door and you’re in a city where galleries, restaurants, bookshops, and quiet neighborhoods coexist without hierarchy. Art isn’t isolated in a district. It’s part of how people live.

Here’s what makes Basel different from other art cities: the museums don’t compete. They operate at completely different frequencies.

Kunstmuseum Basel spans centuries—Old Masters to modern. It moves slowly, deliberately. You can spend an afternoon with Renaissance paintings and leave feeling like you’ve had a conversation, not a transaction. The collection is comprehensive, which sounds like a bureaucratic term but it’s actually important. You’re not seeing a greatest hits version. You’re seeing how painting evolved as a practice, which teaches you to see differently.

Kunsthalle Basel feels like you’re walking through someone’s argument about what contemporary art should be. The exhibitions change. The space is designed to make you think, not to make you comfortable. You’ll walk out of it disagreeing with something. That’s the point.

Museum Tinguely, housed in a Renzo Piano glass pavilion overlooking the Rhine, is kinetic sculpture as a building. The structure itself moves—light changes, perspectives shift as you walk through it. You’re already thinking in movement before you even see the sculptures inside. Tinguely’s work—machines that move, that make noise, that sometimes break—feels like the opposite of most museum objects. These pieces want to do something, not just exist. Sitting in the café overlooking the river, you can watch the light move across the water while absorbing what you’ve just seen.

Now here’s the thing that separates Basel from everywhere else: Schaulager.

It’s a hybrid—part museum, part research storage, part working conservation lab. Founded by the Laurenz Foundation. You can actually see works in conservation, in storage, not in the constant circulation of public exhibitions. You’re seeing the infrastructure of how art institutions actually function. The climate control. The archival systems. The careful handling. The thought that goes into preservation. Most people never get access to this world. Basel lets you see it. Important caveat: Schaulager has limited public access. It’s typically only open during special exhibitions. Check the exhibition calendar before planning a visit—but when it’s open, go.

Walk along the Rhine. The city is genuinely livable. There’s a rhythm that has nothing to do with tourism. People are actually living here, working here, moving through the streets with purpose. The art isn’t a separate experience bolted onto the city. It’s integrated into how the place functions.

End your days at Kunsthalle Restaurant, adjoining the contemporary museum. The wine list is exceptional—it reads like someone’s actual taste, not a corporate wine program. The food is thoughtful without being theatrical. Sit at the bar if you can. You’ll overhear conversations between artists, curators, collectors. Not the performative kind. Actual conversations about what they’ve seen, what they’re working on, what’s working in contemporary practice and what isn’t. You’re not eavesdropping on insider culture. You’re just sitting in a space where people who care about art are talking to each other like normal humans.

Here’s what you understand after Basel: art cities don’t need to be loud about being art cities. The infrastructure speaks for itself. The museums are there. The galleries exist. The collectors are present. The artists are working. When all of that is just the baseline of how a place functions—not the exception, not the spectacle—that’s when you’re actually in an art city. Not a place that has art. A place that thinks in art.

These destinations work because they’re not offering you a “curated experience.” They’re offering access to how people who actually live with art *actually live*. No narrative. No sequence. No “journey.”

Just five places where, if you show up quietly and pay attention, you’ll see things most travelers miss—not because they’re hidden, but because they require you to think differently about what travel can be.

The luxury isn’t just in the hotel (though the hotels are excellent). It’s in being alone with meaningful work in spaces designed for that solitude. It’s in meeting artists while they’re creating. It’s in understanding how a place thinks—through its food, its architecture, its art, its rhythm.

You don’t need to do all five. You probably shouldn’t. Pick the one that feels least familiar. Stay long enough for it to stop feeling new, and let the art, the light, and the people teach you what you came for.